Forget phishing attempts and AI deepfakes – one of the biggest challenges for merchants today is misuse and confusion over how we define fraud.

Fraud in financial services is specifically defined as the intentional act of deception for personal or financial gain, typically involving misrepresentation, concealment of information, or unauthorised actions.

Regulators such as the FCA (UK), MFSA (Malta), and the Bank of Lithuania adhere to international standards from the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), EU Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Directives, and other frameworks. They emphasise that fraud must involve criminal intent and cause actual harm. It is a serious offence with legal consequences, not simply a transactional dispute or an administrative issue.

Yet despite this, under the card scheme’s chargeback frameworks, such cases are routinely processed as fraud. According to the card schemes, friendly fraud represents 50–75% of all fraud-related chargebacks in certain sectors. It’s a staggering figure that reveals how often cardholders exploit dispute mechanisms not because of criminal fraud, but because of convenience or regret.

Card schemes are misusing the term ‘fraud’

The card schemes’ policies force cardholders to falsely label legitimate transactions as fraudulent. For example, when a cardholder forgets to cancel a subscription and wants a refund, but the transaction was protected by 3D Secure (3DS), the only way to initiate a chargeback is by declaring it as fraud. This manipulative structure invites dishonesty into the system and misrepresents what fraud actually means.

Even worse, merchants have no opportunity to dispute or contest these fraudulent claims. The cardholder’s assertion is treated as the absolute truth, regardless of the merchant’s evidence, the contract, or the service terms.

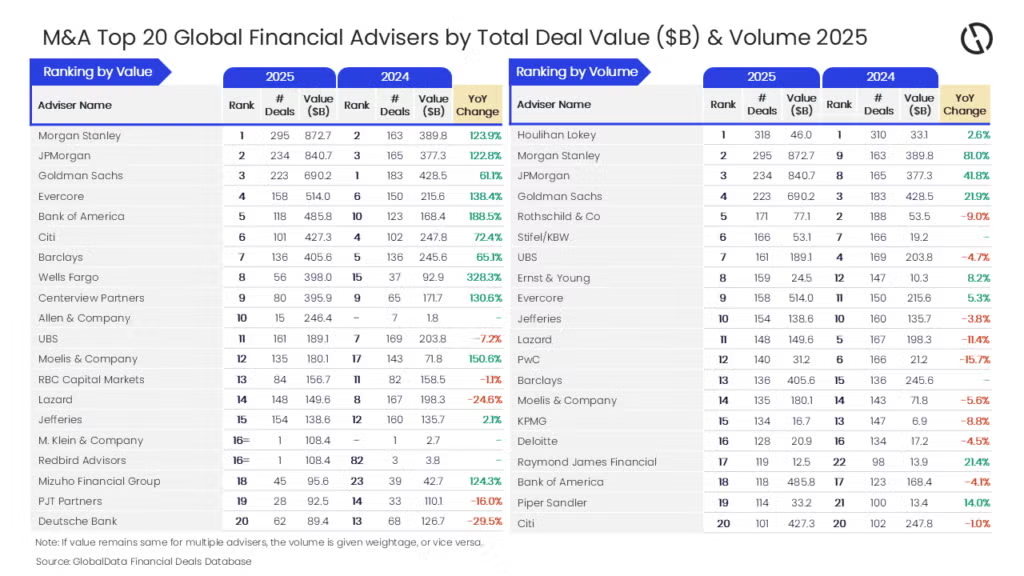

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThere is no requirement for the issuer to collect any substantive proof, nor is there a legal requirement to report the alleged fraud to law enforcement. A criminal offence can be registered simply by pressing a button, and no one, not even the supposed fraudster, is investigated or held accountable.

So who’s responsible?

If these fraud cases were actual criminal offences, why are the supposed fraudsters not investigated or prosecuted?

Both card issuers and acquirers conduct rigorous Know Your Customer (KYC) due diligence. The full identity of every cardholder and merchant is known – verified through passports, utility bills, residency documents, and company ownership records. If card payment fraud were truly a crime, arresting and prosecuting these individuals would be a straightforward matter.

The truth is that the overwhelming majority of these so-called frauds are not fraud at all. And ironically, the true fraudulent activity is increasingly committed by the cardholders who initiate false claims, enabled by a system that not only tolerates friendly fraud but actively encourages it.

In such cases, the card schemes and issuers are complicit, facilitating and legitimising false claims for the sake of user convenience or to shift liability away from themselves.

VAMP is creating an unfair system

Take, for example, Visa’s Acquirer Monitoring Program (VAMP), which is now penalising acquirers and merchants for excessive fraud levels – fraud that is often just mislabelled as friendly fraud.

VAMP’s design is actually a form of competitive discrimination, as it measures an acquirer’s fraud ratio as a percentage of total volume. Large acquirers with massive volumes can absorb fraud without surpassing thresholds. Smaller acquirers, however, are disproportionately affected and far more likely to be non-compliant, leading to assessment fees, reputational damage, or restrictions on their operations.

Acquirers serving subscription-based merchants are especially vulnerable. These merchants naturally experience higher chargeback rates due to recurring billing, trial periods, and consumer forgetfulness. Yet, regulators often fail to understand that these so-called frauds are not crimes. Instead, they may wrongly view the acquirers as risky or non-compliant, potentially restricting or revoking their financial services licenses.

This is a systemic misrepresentation of risk and fraud, driven by flawed definitions and enforced through punitive programs like VAMP. It damages honest businesses while failing to address the root cause of the issue. While there’s a lot of good that Visa is doing right now for both small and large acquirers, it needs to rectify this problem as soon as possible.

A better way forward

Rather than penalising merchants and acquirers, the industry must rethink how it handles consumer disputes and defines fraud, for example, with any of the following:

- Enable cancellation of subscriptions directly in banking apps or card issuer portals.

- Create a new chargeback category for “consumer disputes” that does not require labelling transactions as fraud.

- Require supporting evidence for fraud claims, including optional police reports or formal declarations under penalty of perjury.

- Allow merchants to respond to fraud claims and provide context, especially in cases involving digital goods, subscriptions, or recurring services.

- Encourage regulatory oversight of card schemes to ensure compliance with legal standards and fairness principles.

Friendly fire

The card schemes’ fraud programmes are built on a distorted definition of fraud. It punishes acquirers for chargebacks that arise from cardholder behaviour, while providing no meaningful recourse to the affected merchants. It creates regulatory confusion, distorts competition, and undermines the trust between financial institutions and their customers.

The financial authorities across Europe and the card schemes need to rethink how fraud in the payments world is handled and find ways to prevent the misuse of fraud classifications. A new framework must be established—one that distinguishes between criminal fraud and consumer disputes, respects the rights of all parties, and holds the real bad actors accountable.

Without this, card schemes will continue to shift blame to the wrong side of the transaction. Regulators may continue to unknowingly support a system that incentivises fraud, punishes innovation and discriminates against smaller players

Johannes Kolbeinsson is CEO and co-founder of PAYSTRAX