The increasing automation of business payments is opening up opportunities for fraudsters both inside and outside corporations. Due to the growing volume of electronic transactions and lower levels of accounts payable staffing, payment fraud can go undetected for longer. Robin Arnfield reports

While the economic downturn is a driver for criminal activity, it also provides corporations with incentives to increase efforts to cut their fraud losses. Regulators seeking to protect banking systems, cut funding to criminal and terrorist organizations, and prevent corporate bribes, are adding to the pressure on corporations to fight fraud.

Julie Conroy McNelley, senior analyst, fraud and risk, at US-based consultancy Aite Group, stresses the continued importance of the human factor – for example, staff training and vigilance – in preventing corporate fraud. But technology also plays a major role in policing business payments. Technology automates the scanning of compliance watch-lists such as databases of money-launderers and individuals on government sanctions lists, and helps detect anomalies that may indicate fraudulent transactions.

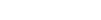

Banks increasingly look to fraud prevention and anti-money-laundering (AML) technologies to help them comply with regulations and prevent fraud losses and reputational damage, Conroy McNelley says. “In August through October 2011, we interviewed 19 out of the 25 top financial institutions in North America,” she says. “Our survey found that most are expecting to spend more on fraud prevention in the next two years, and most of this spending will be on technology.”

Sources of fraud

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData“While fraud attempts on corporations from outside are more frequent, the potential loss per external attack is smaller than the potential loss per inside attack,” says Ben Knieff, director of fraud product marketing at US-based financial crime prevention software vendor NICE Actimize.

“Because insiders know their employers’ controls and how to move through them, they can manipulate multiple systems and processes and mount dramatically large and complex attacks,” says Knieff. “NICE Actimize finds examples every week of inside attacks ranging from $100,000 to $1 million. The payments industry’s move to straight-through-processing (STP) creates opportunities, especially for insiders, to create false suppliers and to direct payments to these suppliers. The rise in automation means that fewer people in accounts payable are involved in checking transactions, which makes life easier for fraudsters.”

For outsiders, cybercrime offers an effective way to steal from corporations. According to PwC’s 2011 Global Economic Crime Survey, 40 percent of US corporations participating in the survey experienced some form of cybercrime such as malware, phishing and intellectual property theft in 2011.

One type of external attack which NICE Actimize is seeing frequently is ‘spear phishing.’ This involves criminals using emails, telephone calls, Facebook or LinkedIn to target individuals within corporations who have authority to initiate payments. These individuals are sent a legitimate-looking email containing malware, for example hidden key-logging software. Clicking on a link in the email activates the software on a corporate computer, allowing criminals to obtain the firm’s bank account credentials and to execute wire and ACH transfers – a process known as corporate account takeover.

In Aite Group’s August-October 2011 survey of North American financial institutions, malware was listed by participating banks as the number one source of pain, says Conroy McNelley. “Survey respondents told us that corporate account breach is like being hit by a bolder,” she says. “The dollar value of outside fraud may be smaller than insider fraud, but cybercrime incidents grab people’s attention.”

Banks’ security policies

US banks are not legally required to reimburse their corporate customers for losses suffered due to online fraud, as they are in the case of consumer accounts. However, if they decide not to absorb the losses, they risk reputational damage and potential loss of clients, Conroy McNelley says.

While the risk of reputational damage might prompt banks to cover corporate customers’ losses from account takeover attacks, this cannot be assumed in all cases. Consequently, corporations need to take steps to secure their banking transactions.

“All electronic transfers must have a second layer of approval within the corporation,” says Stephen Markwell, J.P. Morgan’s treasury services executive director. “Even if fraudsters do penetrate your payment system, they will be thwarted by this. Segregate duties to prevent internal fraud, so that different people are involved at each stage of the payment cycle. Also, segregate your bank accounts, so that each has a specific purpose, for example one account for cheques and one for ACH. This makes it easier to spot exceptions that may be fraudulent.”

“It’s very important for corporations to be aware of their bank’s security policy,” says Terry Austin, CEO of Los Altos, California-based Guardian Analytics, which provides the FraudMAP online fraud prevention service to banks. “This means knowing what online security tools the bank is using and what responsibilities the bank undertakes.”

Austin says many US banks do not comply with best practice in corporate account security. However, the situation is changing as new US regulations are introduced to combat the risk of corporate account takeover, he notes.

In June 2011, the US government’s Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) updated its Internet Banking Authentication guidelines, originally issued in 2005, and told federal bank examiners to formally assess financial institutions’ compliance with these new guidelines from January 2012.

FFIEC recommendations for business banking now include the use of multi-factor authentication involving a hardware device as well as user name and password; security controls such as fraud detection systems that examine customers’ transaction history and behaviour before approving payments; and additional authentication for system administrators who are able to change business banking users’ settings.

As a result of the FFIEC’s new guidelines, Guardian Analytics is seeing faster adoption of FraudMAP, which analyses Internet banking users’ transaction behaviour in real time to detect suspicious activities, Austin says. “We have seen our (bank) customers gaining market share because they promote the strength of their fraud prevention system,” he says.

Guardian Analytics provides FraudMAP on a Software as a Service (SaaS) basis to banks. “FraudMAP’s algorithms are automatically updated every week by Guardian Analytics, based on known fraud cases,” Austin says.

Like Guardian Analytics, NICE Actimize supplies its fraud prevention technology to banks. “Our technology scans payment data, looking for patterns in order to identify potentially suspicious links, for example between individual employees and wire transfers to unusual destinations or suppliers,” says Ori Bach, NICE Actimize’s director, corporate security and case management solutions. “The challenge is to do this it on a large scale, so you can identify patterns. The fraud might involve more than one account, and there might be 20-50 smaller fraudulent wire or ACH transfers. You have to look at all these transactions together. Also, as fraud prevention and AML detection systems move to real-time prompts about suspicious transactions, the challenge is for the human response to occur in real time.”

Combining anti-fraud and AML

Although payment fraud represents a different category of financial crime to money-laundering, terrorist funding, and bribery, the technologies used for detection are related. A number of vendors, including Memento, NICE Actimize and SAS, have created platforms that can be used for simultaneously detecting different categories of financial crime.

“Combining AML and anti-fraud is most successful when done at the technology level where the same analysis engine is used and the same techniques of pattern and behaviour analysis are deployed,” Conroy McNelley says.

However, this exercise can break down if employees in different teams are forced to work together. “Where we see success in integration of AML and fraud prevention is in newer organisations where there aren’t established processes and territories,” Conroy McNelley says.

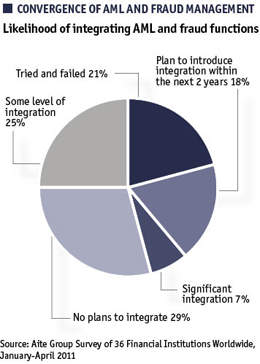

“There is no clear-cut answer as to whether AML and fraud prevention functions will increasingly merge over time,” warns Aite Group’s June 2011 report AML and Fraud: Don’t Order the Wedding Cake Yet. “However, the integration efforts that focus on the sharing of data between the AML and fraud prevention teams appear to have the most momentum.”

“If one department in a firm is looking at fraud connected to a supplier, it needs to know if the AML team has found a change of ownership in the company under investigation,” Bach says. “There is a huge benefit from the two departments working together.”

“The supply chain is an important area of concern,” says Robert McKay, managing director of Accuity, a US-based AML data screening provider. “When establishing a relationship with a supplier, the corporation needs to perform due diligence and carry out regulatory checks. It wouldn’t want relationships with criminals, nor would it want links to a firm that had an undesirable investor such as a dictator. That is why corporations are setting up robust checks, not just for AML compliance, but also for compliance with anti-bribery legislation such as the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (James – this Act prohibits the payment of bribes to win contracts), and lists of sanctions against politically-exposed individuals and organisations such as the US Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) database.”

Accuity’s Compliance Link system monitors 70 lists of prohibited trading partners from the United Nations, the European Union, HM Treasury in the UK, and various US government agencies. “Virtually every developed country has a list,” says McKay. “Accuity is seeing growing demand for Compliance Link, both in developed countries where compliance is mandatory and in developing countries where legitimate organisations want to be seen to be employing best-practice solutions.”

Technology alone not enough

“Fraud prevention is equal parts art and science,” says Conroy McNelley. “We are seeing organizations wanting to use anti-fraud technology to automate and create efficiency. But no-one is looking to eliminate the human element.”

Besides making sure that their bank uses fraud prevention software, corporations should also work with their bank to train the corporations’ employees, Austin says. “Typically, the better banks provide advice and education to their clients’ employees about risk and how to avoid phishing and malware,” he says.

The most important weapon against payment fraud is conducting due diligence, says Andrés Otero, a managing director at US-based business intelligence firm Kroll. “It isn’t enough to just tick the boxes for regulatory compliance, and it’s not good enough to check employees at the start of their employment,” he says. “Employees who manage payments, suppliers and customers have to be monitored regularly.”

Otero says that, while verifying foreign trading partners against official watch-lists and databases such as Dun & Bradstreet is very important, this is no substitute for having local intelligence. “In many countries, you need local eyes and ears to give you an accurate portrait of your trading partners,” he says. “This local due diligence is an important part of what Kroll does for its clients. We have 3,500 consultants in 65 offices in 27 countries.”

“A lot of corporations think there is a magic bullet, a technology that will deal with fraud,” Otero says. “But the challenge is: what information are they putting into their fraud prevention systems? If you don’t have good information, you can’t get good fraud analysis.”

AFP corporate payments fraud survey

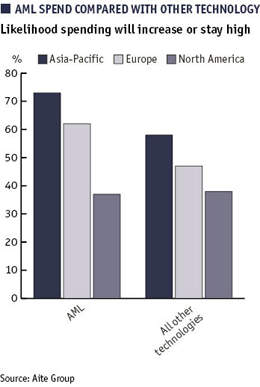

According to the US-based Association for Financial Professionals’ 2011 AFP Payments Fraud and Control Survey, 71 percent of US organizations surveyed experienced attempted or actual payments fraud in 2010. The AFP says that 82 percent of organizations with annual revenues of over $1 billion were victims of payments fraud in 2010 compared to 58 percent of organizations with annual revenues under $1 billion. The AFP’s data is based on a January 2011 survey of its members, which was underwritten by J. P. Morgan. The survey respondents were primarily from the US.

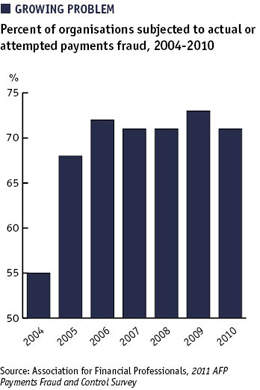

The survey found that 87 percent of organizations suffering payments fraud losses in 2010 did so due to actions taken by outsiders. Ten percent of organizations experienced payments fraud originating from organized crime rings or from third-parties such as vendors, while nine percent of organizations suffered internal payments fraud. Cheque fraud was the most prevalent form of US corporate payment fraud in 2010, with 93 percent of attacked organizations reporting that their cheques had been targeted.

Other payments formats targeted were ACH debits (25 percent of participants affected by fraud – ACH debits involve funds being withdrawn from an account by a third-party); consumer payment cards (23 percent); corporate/commercial cards (15 percent); ACH credits (four percent – a credit transfer initiated by a payer); and wire transfers (four percent).

Corporate account takeover fraud has emerged as a serious threat, the AFP says. Its survey found that 14 percent of respondents experienced this type of fraud attempt in 2010, with 2 percent reporting that their systems had been compromised. In 2009, 4 percent of respondents said they had experienced account takeover fraud attempts.

Chinese wire transfers

In April 2011, the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) issued an alert about unauthorized wire transfers to China.

“Between March 2010 and April 2011, the FBI identified 20 incidents in which the online banking credentials of small-to-medium-sized US businesses were compromised by malware and used to initiate wire transfers to Chinese companies located near the Russian border,” the FBI stated.

“As of April 2011, the total attempted fraud amounted to $20 million, and the actual victim losses were $11 million.”

The unauthorised wire transfers ranged from $50,000 to $985,000 in value, the FBI said.

In addition, the fraudsters sent domestic ACH and wire transfers to money mules in the US within minutes of conducting the overseas transfers. The domestic wire transfers ranged from $200 to $200,000, the FBI said.